How the world’s most famous vampire ended up in Essex

The evidence of the real-life inspiration for Dracula’s English home, Carfax.

Since early May I’ve been reading Bram Stoker’s ‘Dracula’ via email, in real time as it happens in the book. That is to say, the clever folks at

created , a newsletter that shares the novel in small, digestible chunks, on the days the letters, diary entries, telegrams, and newspaper clippings it comprises are dated.I’ve got to say – it’s a great newsletter concept. As someone who now largely works from home and doesn’t have that regular commuting time to read a book, I’ve enjoyed being able to get through a novel as part of my daily inbox management. I’ll miss it when the story concludes next week.

This is the first time I’ve actually read ‘Dracula’. I’ve seen the films and television mini-series based on it. I was even involved in editing a script of it for an ill-fated ‘transmedia’ project in the 2010s. But reading it each morning over my muesli, I learned for the first time that Count Dracula’s Carfax estate – and a lot of the book’s action – is based in Purfleet, Essex.

Five years ago, this probably wouldn’t have meant much to me. But in 2017 I moved further to the east of London, from where Purfleet is just a few miles down the road.

So, I was intrigued to find out if Stoker had based the fictional vampire’s English home on real life landmarks near my own home.

In chapter two, in a diary entry dated 5 May, Jonathan Harker describes the estate he’s acquired on the Count’s behalf:

“At Purfleet, on a byroad, I came across just such a place as seemed to be required, and where was displayed a dilapidated notice that the place was for sale. It was surrounded by a high wall, of ancient structure, built of heavy stones, and has not been repaired for a large number of years. The closed gates are of heavy old oak and iron, all eaten with rust.

“The estate is called Carfax, no doubt a corruption of the old Quatre Face, as the house is four sided, agreeing with the cardinal points of the compass. It contains in all some twenty acres, quite surrounded by the solid stone wall above mentioned. There are many trees on it, which make it in places gloomy, and there is a deep, dark-looking pond or small lake, evidently fed by some springs, as the water is clear and flows away in a fair-sized stream. The house is very large and of all periods back, I should say, to mediaeval times, for one part is of stone immensely thick, with only a few windows high up and heavily barred with iron. It looks like part of a keep, and is close to an old chapel or church… The house had been added to, but in a very straggling way, and I can only guess at the amount of ground it covers, which must be very great. There are but few houses close at hand, one being a very large house only recently added to and formed into a private lunatic asylum. It is not, however, visible from the grounds."

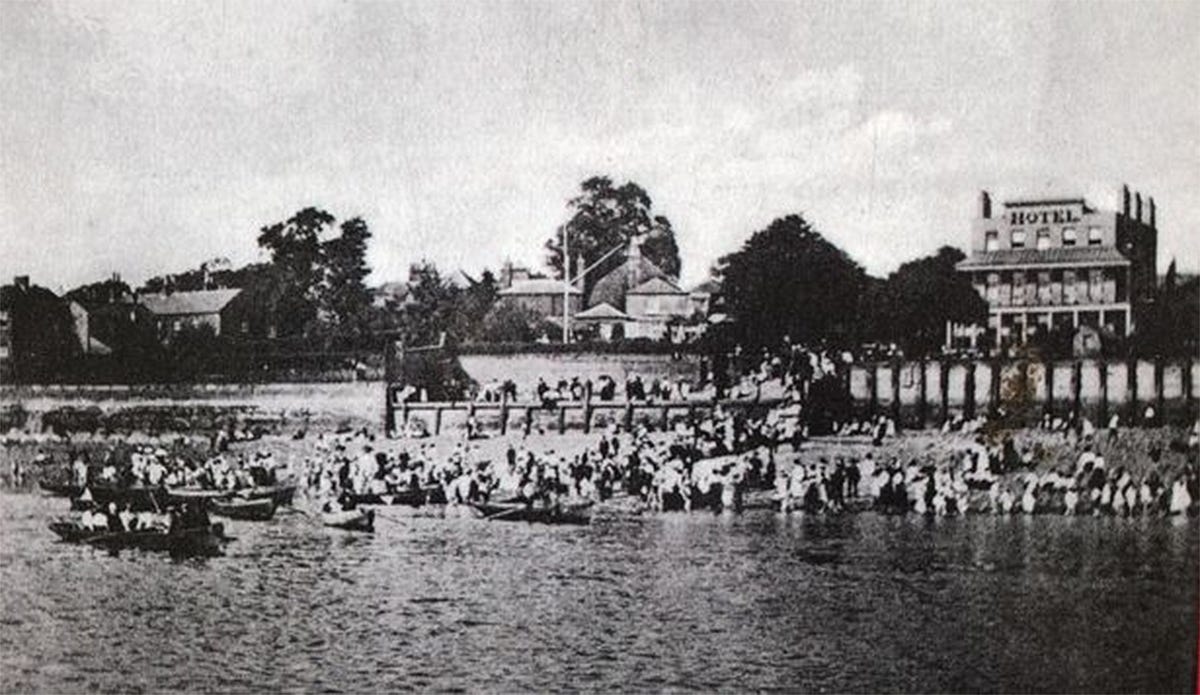

‘Dracula’ was published in 1897. From 1878-1904 Stoker was manager of London’s Lyceum Theatre. Around the same time, Purfleet – then a rural riverside leisure attraction – was a popular location for day trips out of London (a regular pastime of the theatrical set when theatres were closed on Sundays). The waterfront Wingrove’s Hotel – which survives to this day as the Royal Hotel – offered bathing facilities and a famous whitebait supper.

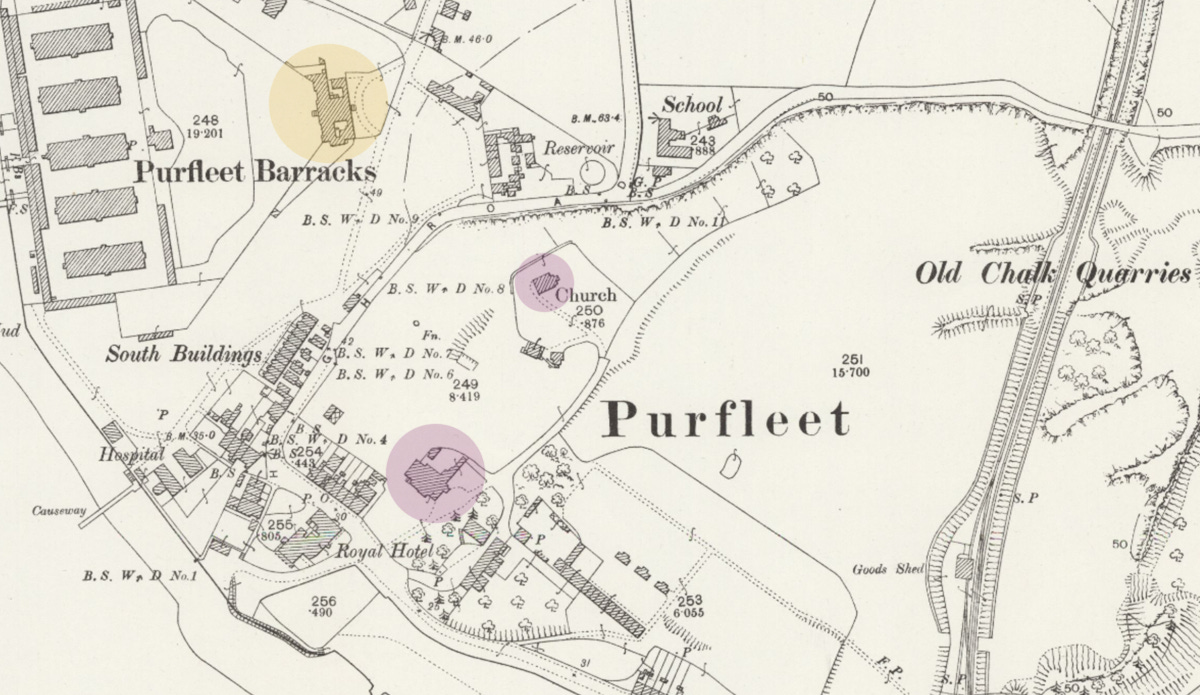

Across London Road, behind the hotel, was Purfleet House, built in 1791 by Samuel Whitbread, founder of the Whitbread & Co brewery and a member of parliament. Local historians agree that Whitbread’s estate (demolished in part in the 1920s and completely in the 1950s) was the inspiration for Carfax.1

The sales catalogue from when Purfleet House was auctioned in the 1920s describes it as having 20 bedrooms, a dining room, drawing room, large paved kitchen, and adjoining store. It had three floors and large cellars.

The estate was set in an old chalk quarry and included a range of outbuildings. As quarrying tends to go below the waterline, this could be the source of the pond mentioned in the book. The five acres of grounds also featured a pleasure garden which was open to the public, including those aforementioned London day-trippers.

Among the outbuildings was a small church located towards the back of the estate, which remains standing, albeit totally derelict.

Today, St Stephen’s Church is located where Purfleet House once stood. Historians say stone from the Whitbread home’s partial demolition in the 1920s was used in the construction of the church.

Some sources I’ve consulted say that a brick and flint wall still standing today on Tank Hill Road – what would have been the lower west side of the Whitbread estate – corresponds with the one described by Jonathan Harker, above. Another contender are the large inner and outer walls which protected the nearby Royal Gunpowder Magazines in Purfleet Barracks.

And the neighbouring asylum in Stoker’s novel? The historians’ consensus is that it was based on Ordnance House, the residence of the gunpowder storekeeper.

Incidentally, the only remaining magazine of the original five (which each stored around 10,000 barrels of gunpowder for the army and navy and were in use for over 200 years from the mid-1700s to mid-1900s) today houses the Purfleet Heritage and Military Centre. The volunteer-run centre features a small exhibit about Dracula’s link to the area.

A house called Carfax did exist in Purfleet until the 1990s, but it was built after ‘Dracula’ was published, so was likely named after the book, rather than the other way around.

Hi Amy

Like you, I read Dracula only relatively recently; before that, I'd only ever seen the films. As I am now writing my own 'inversion' of the story, set in the present day, I have been keen to track down the Purfleet locations.

I do agree with a lot of the suggestions: that Stoker used the LOCATION of Purfleet house, the chapel, the walls and the road, all of which seem to work quite well. What doesn't quite 'click' are the descriptions of the Carfax/Purfleet House as a building. I haven't seen any picture of Purfleet House apart from the one you reproduce, but it doesn't look anything like Stoker's Carfax with its central stone 'keep' and antiquity (partly mediaeval). "The house has been added to, but in a very straggling way, and I can only guess at the amount of ground it covers, which must be very great," Stoker writes. Farther east, beyond High House, there was another old mansion called Stone House, but I haven't seen any pictures of it, so I don't know if that might have been closer to his description of Carfax House. But in reality, it could have come from Yorkshire or Devon or even Stoker's Irish homeland..

Stoker also writes: "It is surrounded by a high wall of ancient structure, built of heavy stones." But real-life Purfleet is not stone country, and the surviving ordnance depot walls - which are about 11ft high - are, as you'd expect built of brick. Some much smaller walls of knapped flints (hardly "heavy stones") can be found round the former Whitbread Estate. However, there is a fragment of a wall with large stone blocks (either removed from a demolished older building or brought in as ship's ballast perhaps?) at the junction of Church Lane and Church Hollow. Maybe Stoker had this in mind.

I'm guessing that Stoker did that novelist's trick of taking a house from one location and putting it in a completely different place. Stoker's friend Arthur Conan Doyle did it in my home village of Stoke D'Abernon (aka 'Stoke Moran') for 'The Adventure of the Speckled Band', where the manor house is in the right place but it's not the building that was actually there. ''Dracula' is fiction, after all!

One final thought: before St Stephen's opened in 1923, the church for Purfleet was St Clement's, which still exists next to the margarine factory in Grays! It's open only occasionally, it seems, which has been its fate for many years. In the 1870s it was "cold and damp and dreary [with a] look of dilapidation". And by the 1890s, when/if Stoker made his visits to the area, "the church was closed for some years and services were apparently not resumed until J W Hayes became vicar in 1902". It was Hayes who later (1920) bought the chapel, Purfleet House and adjoining land and built St Stephen's Church. (All that from british-history.ac/vch/essex/vol8/pp57-74.) So did Stoker have a look round the semi-derelict, damp, dusty St Clement's down the road, adding its "musty" interior to the Purfleet chapel's location?

By the way, that poor old chapel in its brambly wasteland may be getting a new lease of life. The land has been bought by a developer who has promised to repair the Grade II listed structure and turn it into a house, one of six on that land (the others being newbuilds, of course). So perhaps Dracula's chapel will awake from its long slumber. Undead, indeed! I wonder if the new owner will call it Carfax Cottage...