Ill-gotten game and other wartime fun

In between the fighting, there was still time for a bit of mischief.

I’m deep in the middle of data tagging and analysis for my dissertation, and waiting for some feedback on another post I had planned, so today I’m sharing a family story from the past that I hope you will find as amusing as I do.

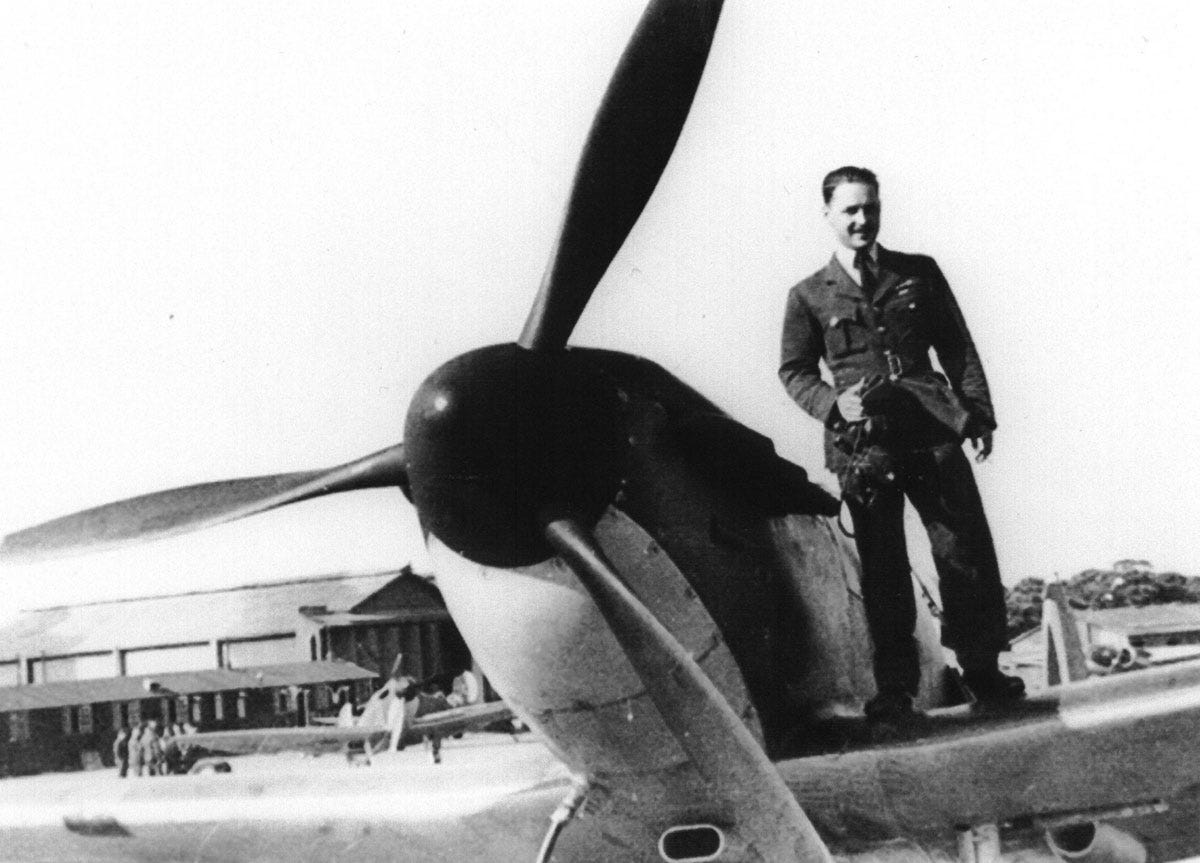

My great uncle, John Connell Freeborn (my paternal grandfather’s brother), was a pilot in the Royal Air Force during World War II. He was a member of 74 ‘Tiger’ Squadron, initially based at Hornchurch in east London. It was from here he took part in the Battle of Britain over the summer and autumn of 1940. He was awarded his first Distinguished Flying Cross in August 1940 and a second in February 1941 for his ‘acts of valour, courage or devotion to duty whilst flying in active operations against the enemy’.

In mid-October 1940, following some rest and recuperation at the end of the Battle of Britain, 74 Squadron returned to the front line, this time based at Biggin Hill in Kent, southeast England. This is where today’s story starts.

As my great uncle tells it in his biography, ‘Tiger Cub: a 74 Squadron Fighter Pilot in World War II’ written with Christopher Yeoman, once a week during their downtime, he and a group of his fellow pilots would take their 12 bore shotguns and go shooting for pheasants.

One day they came across some penned in birds and took advantage of the easy pickings. John Mungo-Park was volunteered to climb over the fence to retrieve them.

As Mungo was chucking the dead pheasants over the fence, the gamekeeper came along and caught him red-handed: ‘What do you think you’re doing!?’

‘O, we just wanted a pheasant, if the owner wouldn’t mind?’

‘Do you know who the owner is?’

‘No, but I’m sure he’s wealthy enough to have a gamekeeper and a pen like this’

‘His name is Winston Churchill. So I’ll be having your name!’

Now, despite my great uncle and his squadron mates being the subject of Churchill’s famous “never in the field of human conflict was so much owed, by so many, to so few” speech just a few months earlier, John never liked him much. He thought the government didn’t pay pilots enough, for a start.

So, while the gamekeeper was demanding Mungo-Park’s name, the others were laughing their heads off on the opposite side of the fence.

‘Don’t tell him Mungo! Don’t tell him your name!’, Peter St John shouted.

Eventually the gamekeeper relented and just asked for the pheasants back. As Mungo-Park scrambled over the fence, my great uncle shouted: “Sod off”, and they all made a run for it.

They took their ill-gotten game to a local pub where the landlady cooked a couple for them and “it was a jolly good meal”.

Not long after, another squadron mate, Walter Franklin, was getting married and fellow airman Peter Chesters was the best man. Chesters had recently been shot down by the Germans and was in hospital recovering from a bullet wound to this leg and ankle. My great uncle drove the pair to the church in Maidstone, Kent, about 30miles away. But as he tells it, “we could barely pass a pub without going in”.

Poor Franklin kept moaning as we made our way to the church, ‘I’m getting married at 3 o’clock’, and Peter would say ‘Well, it’s only 2:30 by my watch and it might be a bit fast’. So we’d have another drink.

Not surprisingly, by the time they got there, everyone was a little worse for wear and the bride’s parents weren’t happy. My great uncle and Chesters were told they weren’t welcome at the reception, but as Yeoman recounts in the biography, “after John retrieved some of Churchill’s pheasants from the boot of his car, the bride’s mother soon came around”.

My great uncle reflected on this period:

My life was full of getting into trouble, or getting Chesters and St John out of trouble. They lived on it.