A unique manuscript on the production and consumption of cheese in 16th Century England

The good, the bad, and the horse-y of the “chiefest” of foods in the Tudor period.

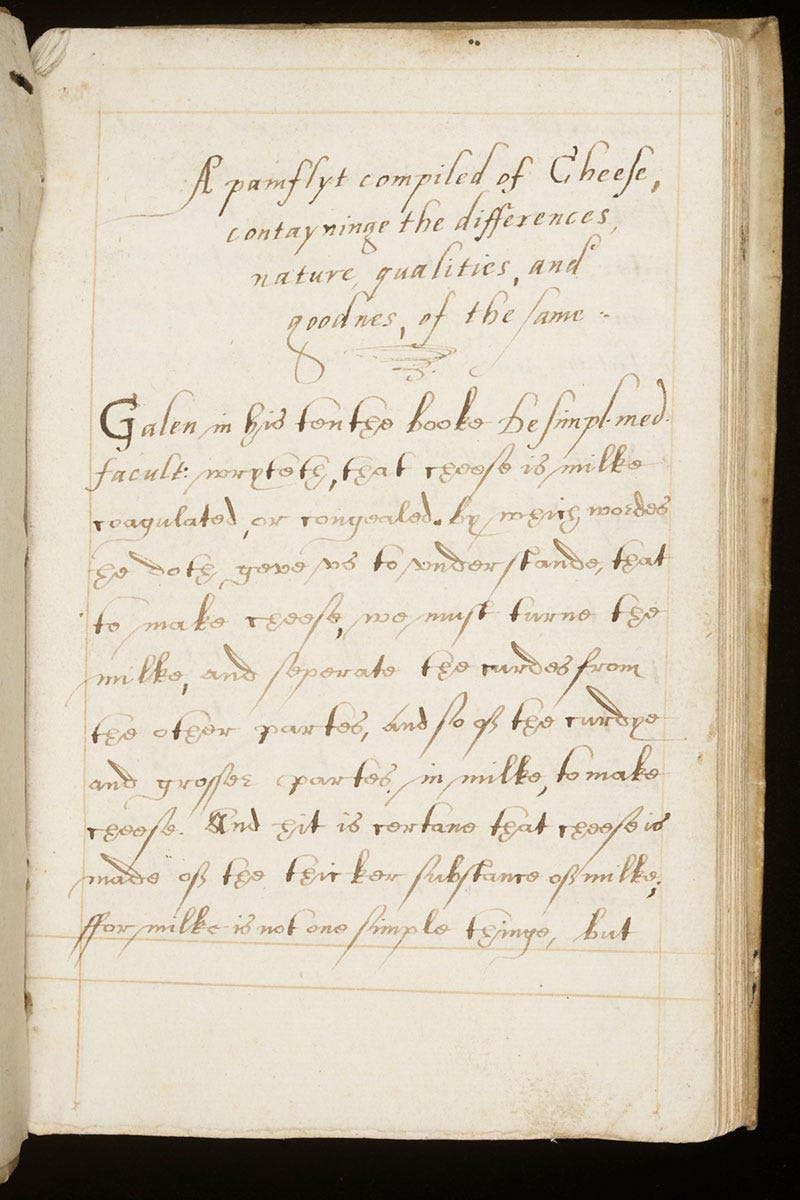

Sometime in the 1580s an unknown author sat down to record their research, knowledge, and opinions about cheese. Called a ‘pamflyt’, it is in fact a 112-page manuscript bound in vellum, and the earliest known English work on the subject.

'A pamflyt compiled of cheese, contayninge the differences, nature, qualities, and goodness, of the same' was bought at auction by the University of Leeds in 2023. It has recently been transcribed by Ruth Bramley, a Tudor re-enactor who gained experience of working with writing from the past through family and local history research.

(NB: I’ve converted all the following passages from the pamflyt into modern English to make them as accessible as possible for everyone.)

Each handwritten page contains around 80-100 words. The contents draw on the works of a host of Greek, Roman, and Middle Eastern physicians, philosophers, and writers, as well as information gleaned following the author’s own “diligent enquiries of country folk who have experience in these matters”.

Food historian Peter Brears says: “I’ve never seen anything like it: it’s probably the first comprehensive academic study of a single foodstuff to be written in the English language. Although cheese has formed part of our diets since prehistoric times, there was still little evidence of its character and places of production by the Tudor era. The pamflyt shows that cheeses of different kinds were being considered, and also studied from a dietary point of view.”

So, what was the state of cheese production and consumption in 16th Century England?

The author tells us that “throughout this little realm of England” there is no other food “that so many do love as cheese” and that many people “do make cheese if not their only, yet surely their chiefest food”.

But rest assured, all this cheese eating does not make English people “sickly and weaklings”; it’s nourishing and makes the population “lusty” with “firm and strong bodies”.

The manuscript starts out mentioning different milks used to make cheese around the world, and includes the clarification that “I have not read in any author that woman’s milk in any place has been used to make cheese” (or dog’s milk, for that matter). But mindful of the work being “fruitful to us, and not tedious”, the author turns their focus to “the milk of beasts […] whereof cheese is made in this our country”.

We learn that cheese made from cow’s milk is the “best and most wholesome”, followed by sheep, goat, and finally, horse. We’re told that in Wales, “they mingle cows milk, ewes milk and mares milk together” and therefore “Welsh cheeses for the most part are of little estimation”.

According to popular verses which tell of the quality of cheeses across England, the “prime and chiefly” cheese-producing location is Cheshire, followed Banbury in Oxfordshire, Llanthony in Gloucestershire, then “Brize north cheeses and Kings north cheeses”, the cheeses of Norfolk, then Suffolk, then Essex, with – as you may expect – Welsh cheese last. (However, the author does go on to say “some Welsh cheeses are as good and commendable as other country cheeses” – presumably the ones that don’t use horse milk!)

The pamflyt considers the maturity of cheeses, how the body’s ‘humors’ and varieties of cheese complement and contrast each other, salty taste versus sour, and suggests that “cheese of middle age when it is come to a full ripeness […] and does not exceed in any one quality” is the best.

The work also deals with the health benefits of cheese.

It hints at the existence of lactose intolerance when it mentions some people “greatly hate cheese” and say it’s “very naughty” and “hurts the stomach”, but ultimately concludes that “if cheese were generally hurtful to man’s nature surely it would offend everybody […] we may gather by this discourse that some one thing does harm one body, and is good and convenient to another”.

From a medicinal point of view, the extremes of the cheese spectrum have distinct benefits: new, soft cheese made with sour milk is good for healing wounds and sores, while old cheese made with lots of rennet – when crushed and mixed with bacon fat – cures knotted joints and gout.

The author also concludes that the optimum time to enjoy cheese is after dinner – is this the origin of our contemporary cheese board tradition?

“By the opinion of all writers, it is best to eat cheese last after other [food ...] at the end of our meals”. This is said to help with digestion by “driving the meat to the bottom of the stomach”. However, be warned: too much wine or other drink along with the cheese will “hinder” its positive effect, instead causing “both cheese and meat to swim in the stomach”.

Dr Alex Bamji, Associate Professor of Early Modern History at the University of Leeds, says the pamflyt is “a substantial piece of work”.

“‘Treatise’ might be a better word to describe it. As with other treatises from this period, the writer has woven together ancient knowledge with their own learning and experience. It’s such a great fit with what we know about how people understood the role of diet in health in the period. Food was useful both to prevent and to respond to illness, and ordinary people had quite a complex understanding of that.”

However, she suggests that the above-mentioned cures may have been included for comic and/or repulsion value, rather than their medicinal effectiveness.

The pamflyt is written, as Dr Bamji describes, in “an incredibly neat hand”, but the author is unknown. The names of three owners are written in it – one of whom was Walter Bayley, a physician to Elizabeth I – suggesting it was passed among the circle of the Dudleys, a family of Tudor courtiers. Brears says: “I look forward to somebody undertaking a PhD on it, because there are clues to its author that demand study in depth: handwriting style, evidence of regional dialects, which modern locations are actually being referred to… There’s so much more to be learnt from this manuscript.”

Fascinating! Had to laugh at the description of cheese as “very naughty” to lactose-intolerant people. And did a double-take advice to mix cheese with bacon fat to cure gout — oh no! I hope Dr. Bamji was right about that being a kind of joke.