What is the UK's human cultural heritage?

Recognising, and protecting for the future, the ‘living expressions inherited from our ancestors and passed on to our descendants’.

It’s World Heritage Day today (18 April), which coincides nicely with an announcement made by the UK government earlier this week that it’s working towards defining an ‘inventory of living heritage’.

I tend to think of the distinction between history and heritage like this: history is what happened, while heritage is the places, the objects, and the customs that still exist today and which help us tell the (hi)story of the past.

Living heritage – or intangible cultural heritage, as it’s formally known – focuses on the ‘customs’ bit: from storytelling, performing arts, and crafts, to festivals, sports, and games, and even our practices connected to the land and food.

Last year, the UK government signed up to UNESCO’s 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage. Part of the process involves member countries creating a list of traditions, skills, and customs practised by its communities.

Inventories will be drawn up across the four nations of the UK (England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland) and later this year the public will be invited to share their nominations for inclusion.

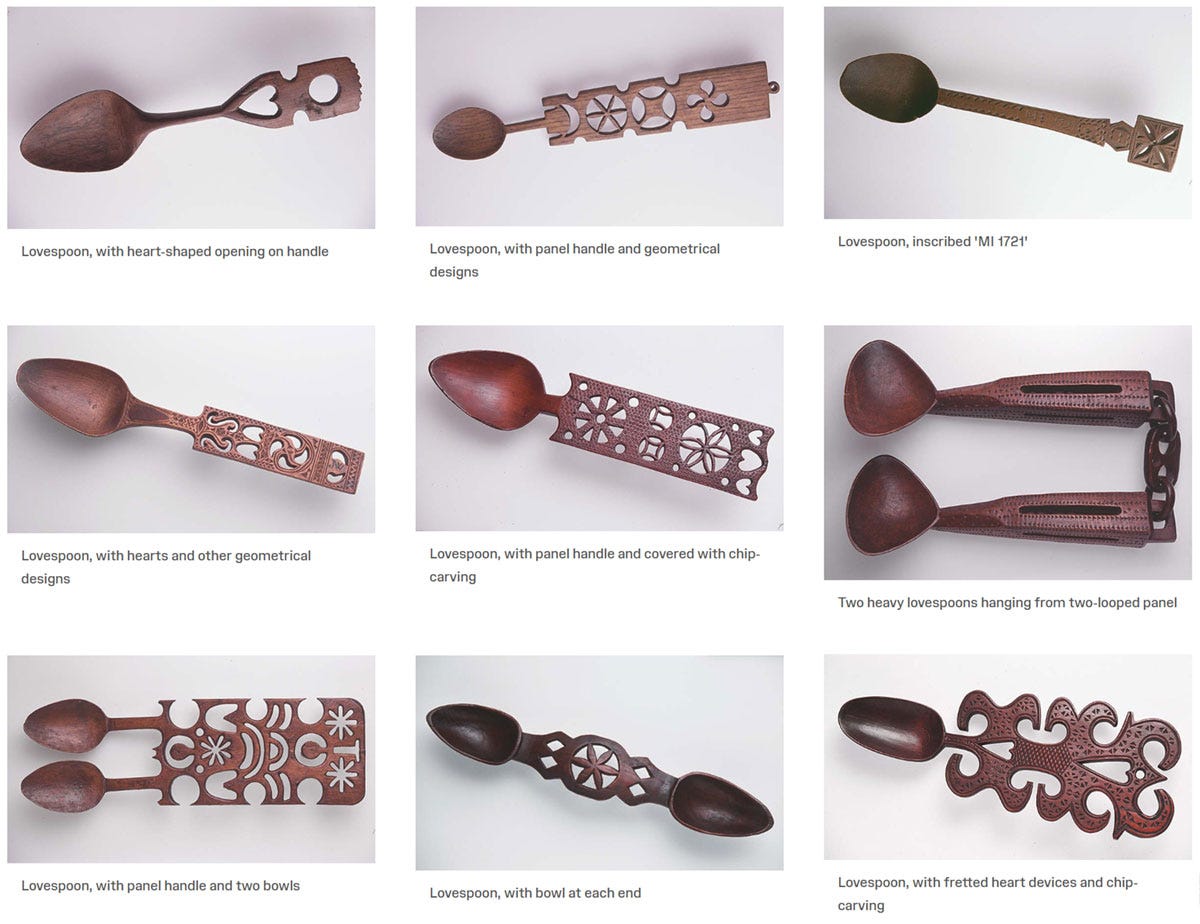

The aim of the inventory and UNESCO list is to capture the quintessential ‘living expressions inherited from our ancestors and passed on to our descendants’. This could include anything from the death-defying cheese rolling that takes place in Gloucestershire in southwest England, to Welsh love spoon carving, the skill of thatching (which is at risk in Northern Ireland), or the prickly-suited Burryman who parades through Queensferry, near Edinburgh in Scotland.

It was David ‘Doc’ Rowe who introduced me to the Burryman, and many other examples of the UK’s living heritage, when I interviewed him about his folk customs archive last year. As you might guess, he welcomes this “serious exploration” of the UK’s “astonishing human cultural traditions” which he has found are often unknown, overlooked, or even treated trivially.

He hopes that recognition will “honour the dedication and legacy of many ‘tradition bearers’ who in some places, despite opposition, continually upheld these customs and to whom we owe a great debt”.

Rowe emphasises that the UK’s traditions and customs are not activities fixed in time, but ones that “exist and evolve in an ever-changing landscape”. They are “spontaneous, vernacular, and organic practices which continually respond to change […] using the best from the past, distilling and embracing elements for the present, but caring for and developing the form for the future”.

They are, indeed, our ‘living heritage’.

What would you nominate for the UK’s inventory of living heritage?