The paintings that couldn’t save a marriage (even if they’d tried to, which we can’t definitively say they did)

The curious, significant history of a series of Tudor period artworks.

The subject of this fortnight’s newsletter came to me via a suggestion that the paintings in question were created to help dissuade Henry VIII from divorcing his first wife, Katherine of Aragon.

It’s a tantalising idea that (as I understand it) is shared reasonably openly within the circle of those who come into close contact the artworks.

But sadly, it’s not a fact confirmed in any of the scholarship. However, that’s not to say Henry, or Katherine, are out of the picture all together..!

(NB: several of the names I mention here have multiple spellings – I’ve gone with the version used most frequently in the sources I’ve relied on to write this story.)

Let’s set the scene

The artworks were commissioned by Robert Sherborn (c.1454-1536), Bishop of Chichester, for his castle in Arundel, southern England, sometime between 1508 and 1526. They’re known as The Amberley Panels (after the name of the castle) and depict eight women from antiquity. There were originally nine portraits, but by 1865 the ninth was described as ‘remaining only in fragments’.

The subjects are known collectively as the Heroines of Antiquity or the Nine Worthy Women. The group first appears in the literary record between 1389 and 1396.

They follow an earlier iteration known as the Heroes of Antiquity/Nine Worthy Men, first documented c.1310. Traditionally, the nine were composed of three pagan (or, classical), three biblical, and three Christian leaders. In the case of the women, later alternative configurations featured Amazon and Middle Eastern queens, and even groups of English leaders such as Boudica, Æthelflæd, and Margaret of York.

The Amberley Panels are particularly special in the canon of ‘Worthies’.

According to independent art historian Karen Coke, not only are they unique in departing from the leaders-only theme in at least one instance, they are the most complete English example dating from the first half of the 16th Century. In an article published in 2007, Coke said “nothing of this type dating from before the 1520s has yet been discovered”.

What are the Amberley Panels?

A series of portraits painted in oil on oak, ascribed to court artist Lambert Barnard (c.1490-1567). Each one measures about 84x115cm and was originally incorporated into a panelled wall in the ‘Queen’s Room’ at Amberley Castle. Also in the room was a series of Heroes of Antiquity/Nine Worthy Men portraits, positioned below the women.

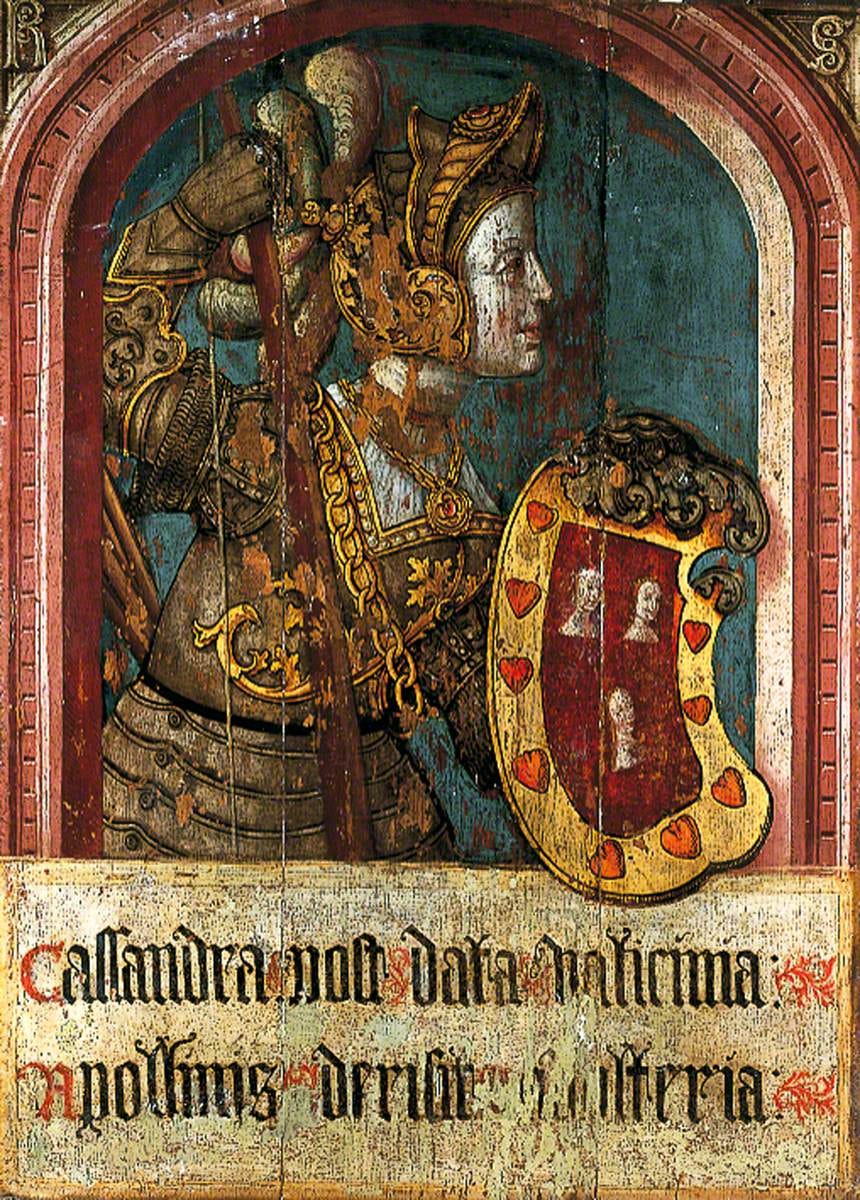

The subjects are: three Amazon queens – Lampedo, Hippolyta, Menalippe; three Middle Eastern queens – Sinope, Thomyris, Semiramis; and (unusually) the Trojan prophetess-Princess Cassandra. An eighth woman is no longer recognisable (but often identified as Zenobia, Queen of Palmyra). The ninth painting doesn’t survive.

Over the centuries, most of the paintings have been damaged to varying degrees, but relying on 19th Century descriptions and sketches, alongside modern analysis, it can be determined that the women all wear gold chains, velvet or damask gowns, and either crowns, headdresses, or helmets. Each carries a shield (and some, weapons), and wear mail and plate armour. They are set below an arch and behind a low wall, and each painting features a descriptive verse in black letter at the bottom. Four of the paintings have red backgrounds and five blue, suggesting they were arranged by alternating colours.

Coke describes them as an idealist representation of medieval femininity (the women are blushing, modestly smiling) that simultaneously communicate a fierce, often violent, history. In a short article for The Novium Museum (formerly the Chichester District Museum) she says: “These women shared various characteristics, some were empire-builders, leaders of armies, monarchs in their own right, sometimes with bloody histories, yet also engaged with the more feminine attributes of charity, mercy, virginity and piety.”

What have they got to do with Henry and Katherine?

The Amberley Panels were commissioned as part of Sherborn’s renovations of his castle. It’s suggested – including by Coke – that this work may have been, in part at least, in anticipation of a visit from Henry VIII and his wife, Katherine.

It’s further suggested that the paintings were designed for the eyes of the King and Queen by the depiction of Hippolyta. She wears a Tudor headdress, holds a bow and carries a quiver containing a single arrow. Coke explains it was a favourite contemporary visual pun on Katherine’s name: Aragon / ‘arrow gone’.

“Katharine would have recognised the flattering reference to herself in the guise of a warrior queen both as a reminder of her frequently armour-clad mother, the uncompromising Isabella of Spain and of her own military career, when in 1513, as acting Regent during Henry's absence fighting the French, she was in titular command of the English armies when they defeated and killed Henry VIII's brother-in-law, the Scottish King James IV at Flodden,” Coke says.

But, alas, Katherine never visited Amberley Castle, never saw the Worthies.

As for Henry, we know that in the summer of 1526 he spent a few days at the nearby Arundel Castle. One of this travelling party, William Fitzwilliam, wrote of dining with Sherborn (at an un-named location) and commented on the place containing 'sundry and diverse devises', which he had not seen elsewhere. Coke explains that a ‘device’ in Tudor terms was a heraldic or curious design, a description that “fits perfectly” the designs on the shields carried by the women in each painting.

Were the Amberley Panels intended to show the worthiness of warrior queens, like Aragons? Was it hoped they’d dispel Henry’s anxiety for a male heir? Did the King seek advice from Sherborn – who’d secured the papal dispensation for the then-prince to marry his brother’s widow two decades earlier – about the future of his marriage to Katherine?

We may never know for sure. But even if all these things are true, the paintings nor the Bishop were able to prevent divorce. By the following spring of 1527 Henry was declaring his marriage invalid and setting off a chain of events that would see England break from the Catholic Church in Rome and establish the Anglican Church of England in 1534.

What of the Amberley Panels today?

Following Sherborn’s death in 1536, Amberley Castle changed hands multiple times over the centuries. In 1983 the paintings were put up for auction and acquired by the Chichester District Council, and later went on long term display at the local Pallant House Gallery. Most recently, they’ve been at the Bishop’s Palace in Chichester, but are due to be (or may have already been) taken off display while it’s redecorated.

In 1999-2000, while artist in residence at Pallant House Gallery, artist Joy Gregory produced a series of photographs inspired by the Amberley Panels. In an interview on the gallery website, she explained that she wanted to reinterpret the paintings with “each of the women to have physical characteristics common to the geographical region from which they were thought to originate”.

Tantalizing indeed! Beyond the symbolism of the paintings and the messages they likely portrayed, the idea that someone would go to the expense and effort to have them commissioned on the off-chance they would be seen and then properly interpreted by Katherine and Henry is astonishing and speaks to the role of art in communication and influence. Great piece!