The ‘extinct’ wonder plant of the ancient world, rediscovered

It made food taste better and had multiple medicinal properties, but now that therapeutic value could put it at risk again.

Silphion was renowned across the Mediterranean around two and a half thousand years ago.

It was written about by Herodotus, Hippocrates, and Pliny the Elder. So revered was it, that it graced the coins of the Cyrene region, in what is now Libya. Indeed – it was the main economic commodity of the area for centuries.

Theophrastus of Eresos (c370-285 BC), dubbed the ‘father of botany’, described silphion – including the use of “juice” from its stalk and roots for medicinal purposes – in his famous work, 'Enquiry into Plants’.

It was variously attributed as a remedy for ailments ranging from a hernia to heart disease, toothache to tetanus, and was used as an aphrodisiac as well as a contraceptive.

It was also a prized spice, mentioned in recipes that survive from the classical era, including in the famous 4th Century AD cookbook, ‘Apicius’.

But its culinary and medicinal value was not enough to prevent its demise.

In chapter 15, book 19 of his 'Naturae historiae' (the 37-volume treatise was completed in 77AD), Pliny wrote:

“…a very re-markable plant, known to the Greeks by the name of ‘silphion,’ and originally a native of the province of Cyrenaica. The juice of this plant is called ‘laser,’ and it is greatly in vogue for medicinal as well as other purposes, being sold at the same rate as silver.

For these many years past, however, it has not been found in Cyrenaica, as the farmers of the revenue who hold the lands there on lease, have a notion that it is more profitable to depasture flocks of sheep upon them.

Within the memory of the present generation, a single stalk is all that has ever been found there, and that was sent as a curiosity to the Emperor Nero.”

No specimen of silphion exists to confirm its scientific identity. That, combined with its various remarkable attributes, makes it an appealing mystery for scientists.

Mahmut Miski is a professor of pharmaceutical sciences. Since 1980 he’s been investigating the biologically active compounds of 26 species of plant from the genus Ferula, growing in Turkey.

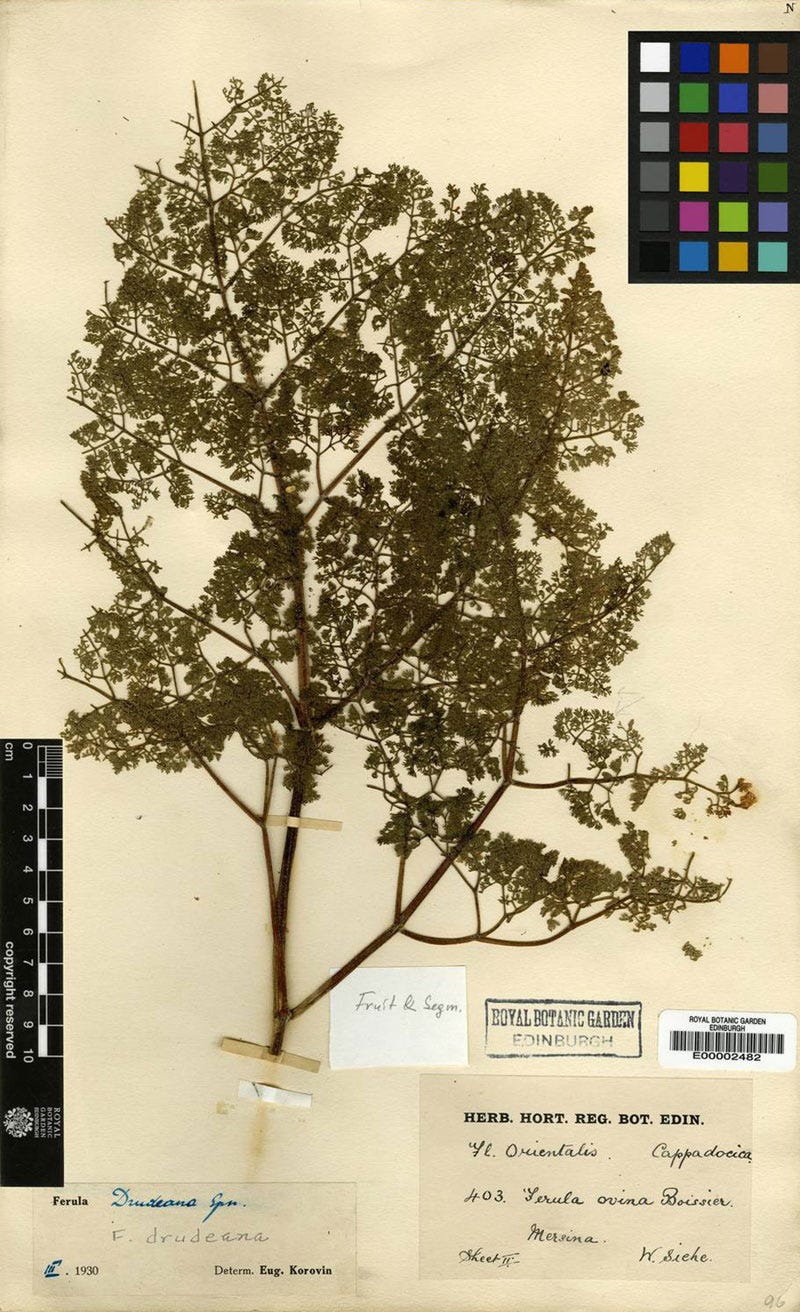

Among them is one called Ferula drudeana. Around 2011, Professor Miski began closely examining it as a potential new medicinal plant and noticed its similarities to the long-lost silphion.

“The silphion plant was one of the earliest known medicinal plants in the history of mankind. It was the ‘ginseng’ of the Western world. In addition to its countless medicinal properties, the silphion plant was also used as a spice, which doubles its economic value compared with the ginseng plant,” Professor Miski says.

In a scientific article published in 2021, Professor Miski sets out evidence that “strongly suggests” Ferula drudeana – which grows in just three locations of central Anatolia (Turkey) today – “presumably is the silphion plant”.

All three locations have links to former Greek villages, giving further credence to his findings. Professor Miski thanks “the ancient smugglers who presumably brought the seeds of the silphion plant to Anatolia [so] this precious species may have survived the extinction that its relatives had suffered in the Cyrenaic region of Libya c2,000 years ago”.

The striking similarities Professor Miski has discovered include:

The opposite arrangement of stem leaves of F. drudeana (which is rarely observed in other Ferula species) match illustrations of silphion on ancient coins.

Likewise, the striated appearance of the silphion stem on coins correspond to the resin channels under the surface of F. drudeana’s stem.

The arrangement of the seed pods of F. drudeana match the heart shape depicted on Cyrenaic coins.

Resin (or ‘juice’, as ancients called it) can be obtained from the stalk and root of F. drudeana and contains virtually all of the bioactive chemicals produced by the plant.

Those chemicals contain about 30 compounds (some previously found in other medicinal plants), many of which match the therapeutic claims attributed to silphion by ancient authors.

The scent of the resin – described in ancient texts as “predominant and gentle” – matches the pleasant-smelling characteristics of F. drudeana, which is unlike other Ferula species.

Several other plants have been proposed to be silphion over the years, but none has ticked as many boxes of the ancient descriptions as F. drudeana.

Food historian and archaeologist, Sally Grainger, says silphion was “valued very greatly indeed” as a spice in the ancient world, although recipes and descriptions are not very forthcoming about its specific taste.

“It is very commonly signified in banquet menus where no other seasoning is mentioned. Many recipes require it, and we must suppose that it had a distinctive taste that the gourmet could recognise and be proud to offer to his guest.

“We are not told what it tasted like, but they don't actually say much about the taste of other spices, either.”

She was “thrilled and enthusiastic” to get a chance to cook with F. drudeana last year, albeit using only a very small amount of resin, alongside peeled fresh roots. She described the taste as “intriguing”.

She made several recipes, including:

Laser sauce, which involved dissolving the F. drudeana resin in warm water and blending with vinegar and fish sauce. She says its taste was “green with a hint of spice”.

A lamb and prunes dish using the F. drudeana root, which had a “distinct and pleasant flavour”. Grainger says she and her fellow taste-testers “really wanted to taste it again”.

While Grainger says her cooking trials to date aren’t enough for her – from a culinary perspective – to definitively declare F. drudeana and silphion one and the same yet, she’s keen to try further experiments with larger and more potent samples.

The challenge for Professor Miski and the local custodians of those three F. drudeana sites is preserving and propagating the species.

Basic attempts to grow the plant from seeds have so far failed. Scientific attempts at seed gemination have produced seedlings, but only saplings raised to at least two-years-old have survived replanting in their parent plants’ location.

It’s slow going. Professor Miski believes F. drudeana is a monocarpic species – meaning it only flowers and produces seeds once before dying. Based on the size of the wild-growing plants, he thinks it must take at least nine or 10 years for the plant to reach flowering maturity.

To date, they’ve successfully grown in their experimental plots about as many plants as what currently exist in the wild – taking the total number of known F. drudeana plants to maybe 800 at most.

While they continue to experiment and wait, Professor Miski and co must also keep a keen eye over their shoulders.

F. drudeana’s aphrodisiacal properties and use for erectile dysfunction puts it in danger of extinction once again.

“One of the first Ferula species growing in Anatolia that I investigated in 1980 was F. elaeochytris, which has a reputation for being an aphrodisiac.

“This species had a huge population that could be counted as several thousand individuals growing on Mount Cassius (Kel Dağı in Turkish). When government agencies allowed the collection and marketing of this species by local herbalists, this huge population was almost completely destroyed. It is now extremely difficult to find a single individual growing in the same location.

“In comparison, F. drudeana is an extremely rare species, and it’s not difficult to imagine an impending extinction of the F. drudeana growing in Anatolia if it was subjected to the same destiny as F. elaeochytris.”

And that’s alarming, because Professor Miski says F. drudeana’s potential is so great:

“The propagation and reintroduction of the silphion plant (or a medicinal plant with an equivalent value to the silphion plant) could contribute to and enrich the culinary and health aspects of mankind.

“We may also discover novel biologically active compounds that could lead to new medicines to treat hitherto untreatable diseases.”