Disguising science as watercolour instruction suitable for women

‘She’s an excellent example of a woman who pursued flower painting as a route to something else – in this case, scientific knowledge’.

I do love it when a woman subverts the conventions of her time.

Take Mary Gartside – painter, teacher, and author. She was an unmarried woman in the late 18th and early 19th centuries who disguised scientific and aesthetic explorations of colour theory in books about watercolour painting techniques.

She published three works between 1805 and 1808: ‘An Essay on Light and Shade, on Colours, and on Composition in General’ (1805), ‘Ornamental Groups, Descriptive of Flowers, Birds, Shells, Fruit, Insects etc’ (1808), and an expanded second edition of her first work, retitled ‘An Essay on a New Theory of Colour, and on Composition in General’ (1808).

On first appearances, they seem to fit within the tradition of instructional art guides that were acceptable for women to author in the early 19th Century.

But the veiled and modest language she used obscured what were in fact the first scientific examples of colour theory published by a woman in Britain, perhaps even the whole of the Western world. It was a subject considered the domain of men in this period.

In ‘Learning to Draw: Studies in the Cultural History of a Polite and Useful Art’, Ann Bermingham says: “[S]he is an excellent example of a woman who pursued flower painting as a route to something else – in this case, scientific knowledge as well as a professional artistic career […] The very modesty of the genre obscured the originality of Gartside’s inquiries, and in so doing enabled her to pursue them.”

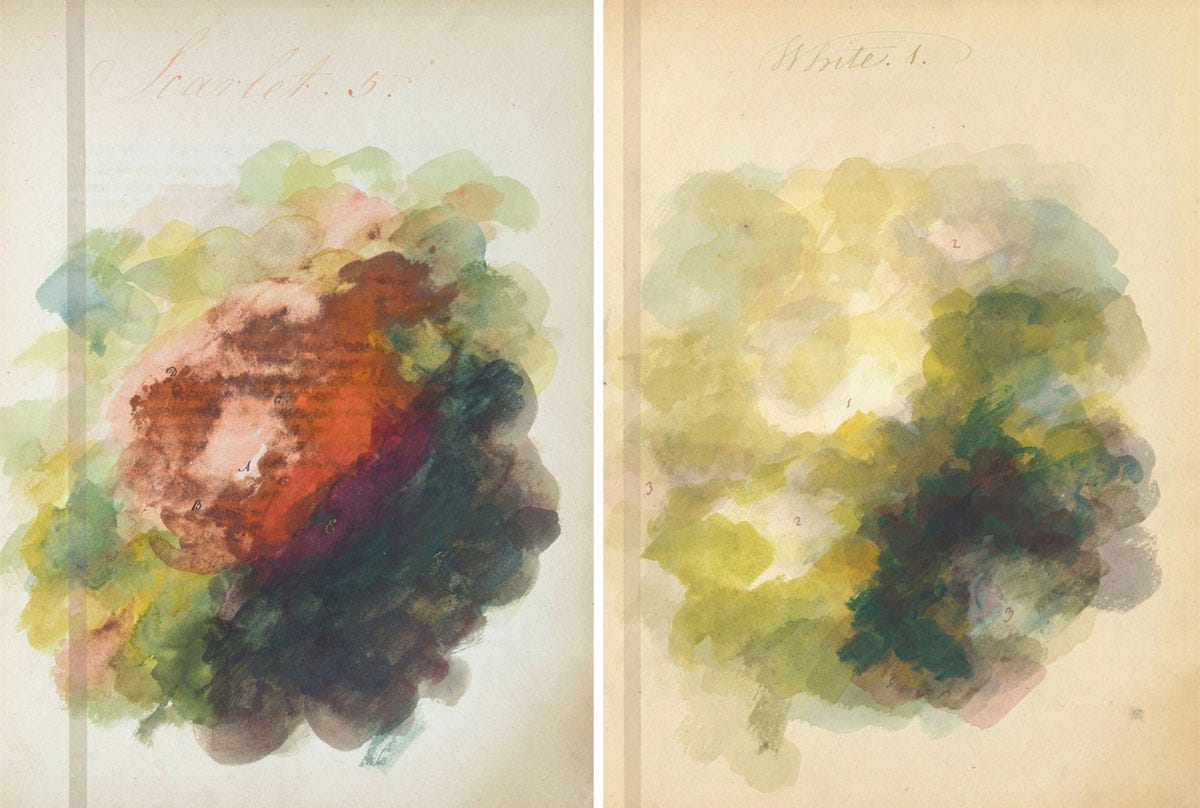

Her ‘An Essay on Light and Shade’, for example – of which only 15 copies are known to survive in libraries and collections around the world – is 54 pages and includes two hand-coloured tables and eight watercolour ‘blots’ that demonstrate her ideas on the arrangement of complimentary and contrasting colours. It references and expands upon Isaac Newton’s famous ‘Optiks’ (1704), in which he experimented with prisms to split white light into the seven colours of the visible spectrum.

In an article for the Journal of Art History and Museum Studies, Alexandra Loske says: “[Gartside] remarks that she does not oppose Newton’s prismatic order, the colour sequence of the rainbow, but argues that colours should be arranged according to their level of brightness, thus making changes to the natural order of colours.”

Gartside included white as a colour in its own right (with pigments for painting, a mixture of all colours produces a muddy brown, rather than white in the case of light) and rearranged the order of ‘rainbow’ colours to suit her theory about the significance of light and shade.

Unfortunately, not much is known about Gartside’s life outside her books. It’s thought she was born in either 1754 or 1755 and died sometime between 1809 and 1819. She is known to have lived in Manchester and London, and exhibited botanical artworks at London’s Royal Academy in 1781 and other art societies up to around 1808 or 1809.

There are no contemporary sources that comment on her work as an artist or a colour theorist. However, in more recent years, her importance has been acknowledged and celebrated:

Her watercolour ‘blots’ have been recognised as early examples of abstract painting and were included in an exhibition alongside JMW Turner at the Kunsthalle in Frankfurt in 2007-2008.

‘An Essay on Light and Shade’ – described as “one of the rarest and most unusual books about colour ever published” – was part of an exhibition at Brighton’s Royal Pavilion in 2013.

‘An Essay on a New Theory of Colour’ was included in an exhibition at London’s Tate Britain in 2024, where it was described as “the first illustrated book on colour published by a woman in the West”.

Loske says: “Mary Gartside’s publications on colour might not have had the critical acclaim and lasting influence of those of some of her contemporaries, but she deserves to be examined within her historical and social context [...] it appears that she was restrained by her gender and genre with regard to a wider readership. However, it is precisely these known constraints that make her case worth investigating in an art historical context. Her theory of colours can be assigned a distinct place in the development of colour theory in Europe.”